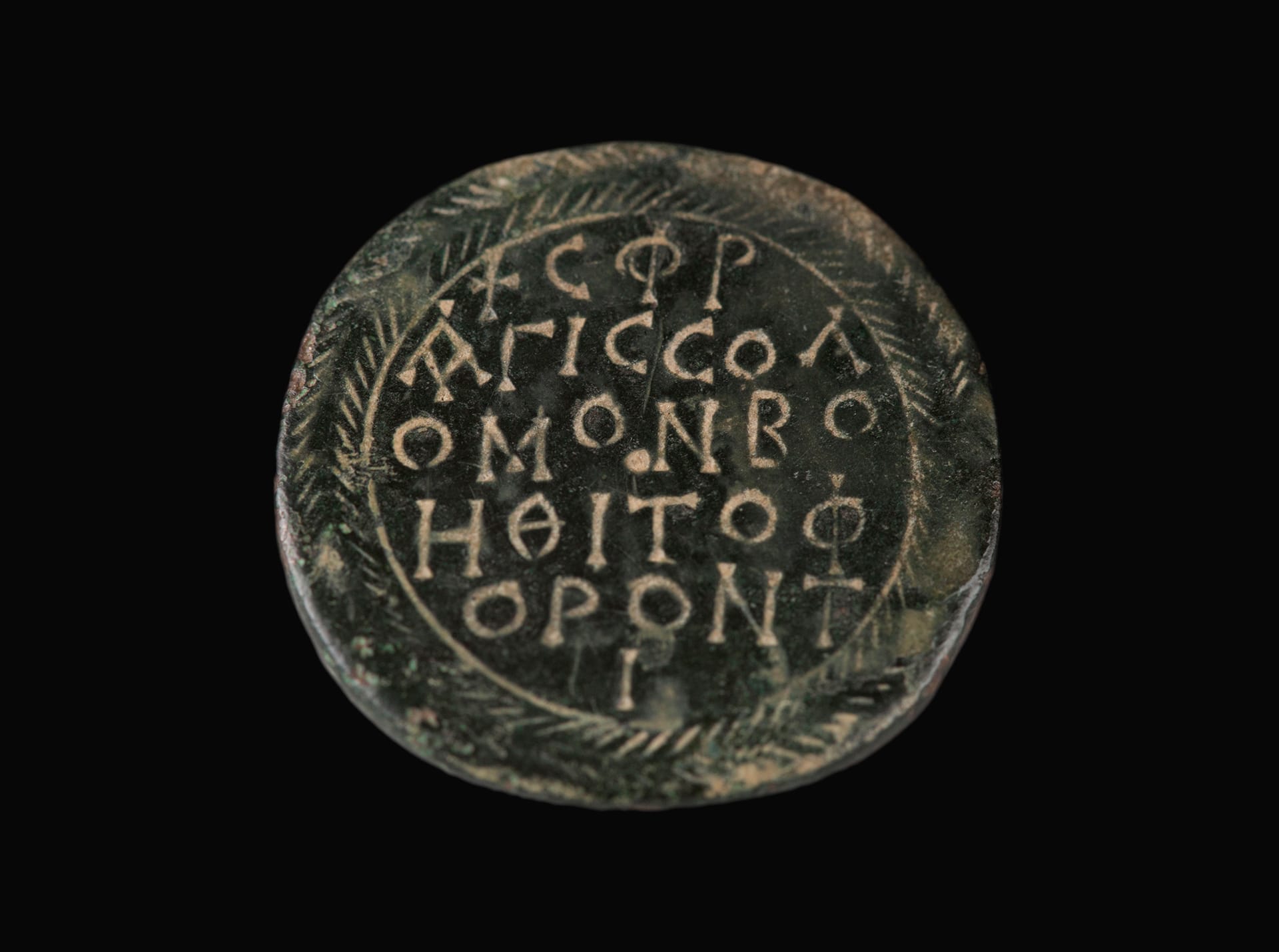

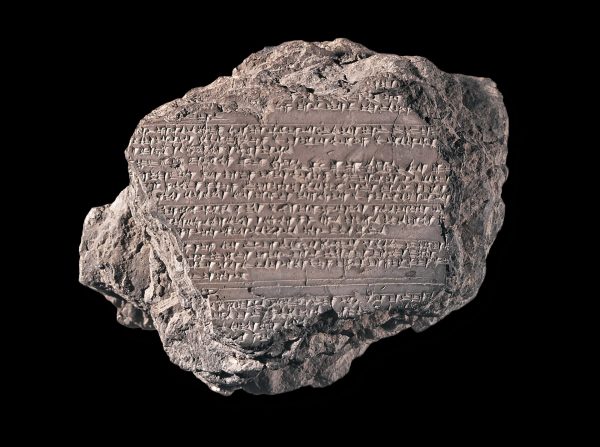

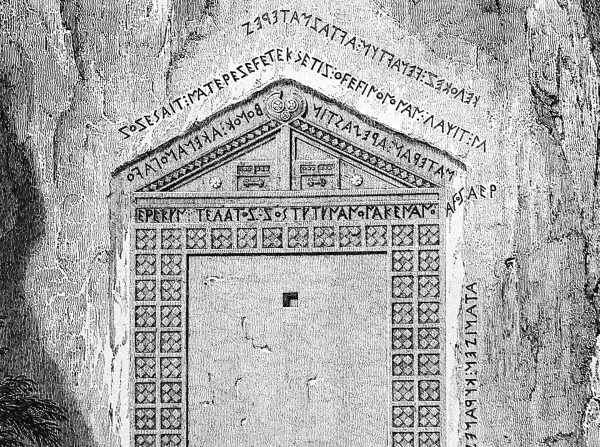

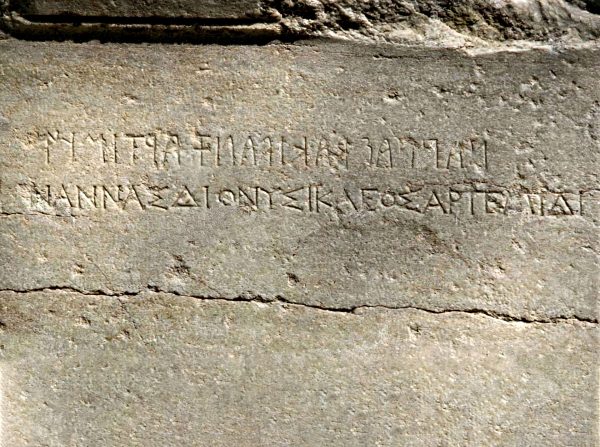

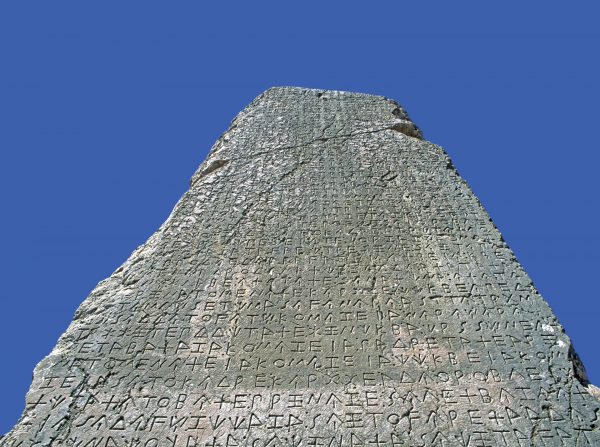

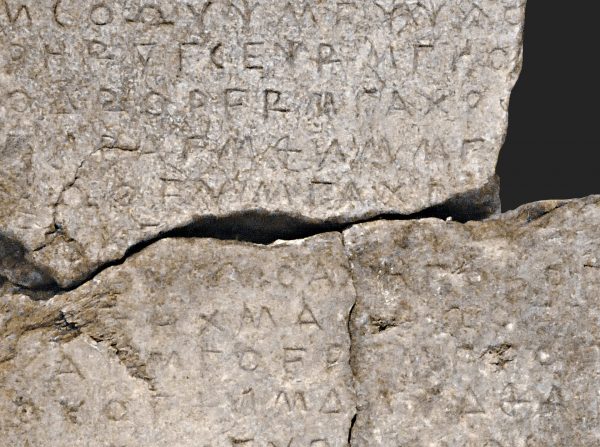

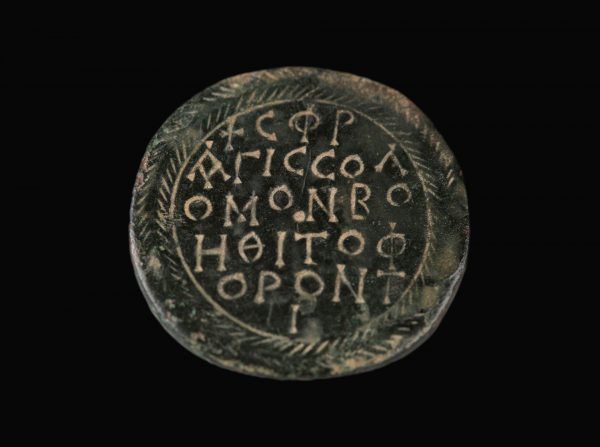

From Alexander the Great onwards (330 BC), Hellenic became the foremost language of communication in the Eastern Mediterranean world. Known as Koine (= common), this dialect of Hellenic underwent certain changes as of 1st-2nd century A.D., such as the pronunciation of β (beta) as “v”; η (eta) as “i”, or the αι (= ai) diphthong as ε (epsilon). At the end of such changes that lasted several centuries, both written and spoken Hellenic evolved and gave birth to a language that strongly resembles its present-day counterpart. For example, formerly read as “Basileus” in its Latin transcription, Βασιλεύς, was now pronounced as “Vasilevs.” Such changes, though smaller, occurred not only in pronunciation, but also in the shape of letters as of 3rd century AD.

In 629 AD, East Roman Emperor Heraclius replaced Latin and introduced Hellenic as the official language of the Empire. Once Hellenic attained this official status and Christianity was embraced in almost all parts of the empire, Hellenic became the language of the East Roman people. After all, the different nationalities living within the Empire were required to speak this language in order to read and understand the Bible written in Hellenic. Thus, Hellenic became the daily language of all the ethnic groups living in the East Mediterranean basin, the north and south of the Black Sea, and the Middle East.