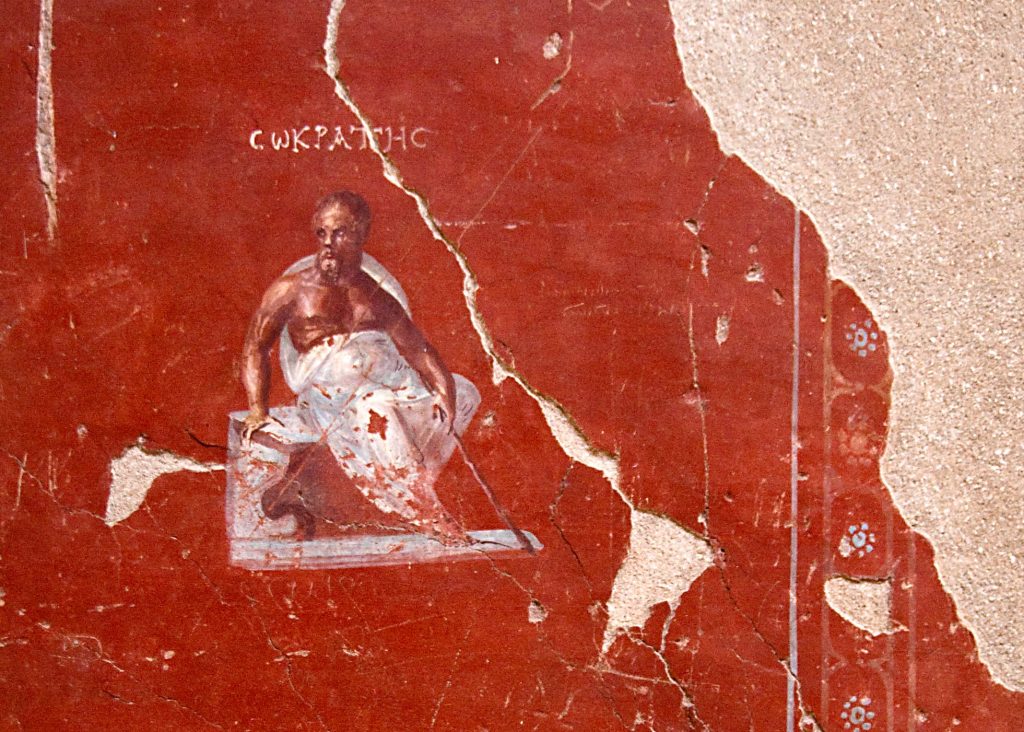

Although higher education in Athens was offered in return for payment, renowned philosopher Socrates never accepted money in exchange for his lessons. He believed he could maintain his freedom by refusing payment and regarded the ones he did as self-serving slaves for having to talk to the individuals that paid them. Alternatively, he justified this by saying the people who taught in exchange for money were required to render services, but that since he never asked for money in exchange for knowledge, he was not obliged to talk to or instruct the people he chose not to. His disciple Plato, on the other hand, argues that humans must receive education for the survival of the soul. Whether they are of Hellenic origin or barbarians, education and philosophy make people happy, shed light upon them, and render them both intelligent and skilled. Hence, Plato advocates that in order to raise a healthy and virtuous generation with souls cleansed of evil thoughts, education and instruction must be provided correctly and properly from infancy onwards.

In all his works, Plato urges people to receive education, particularly in philosophy. According to the philosopher, once trained in philosophy and having internalized it, people shall never need the guidance of others; they will possess a good memory, abide by laws, and grow into happy individuals. According to Plato’s student Aristotle, the main objective education is to make the individual a virtuous and erudite element of the society or the state in which s/he lives. People can only attain happiness when they are educated in this manner. Therefore, lawmakers must handle the issue of education personally and should begin doing so with couples to be married.